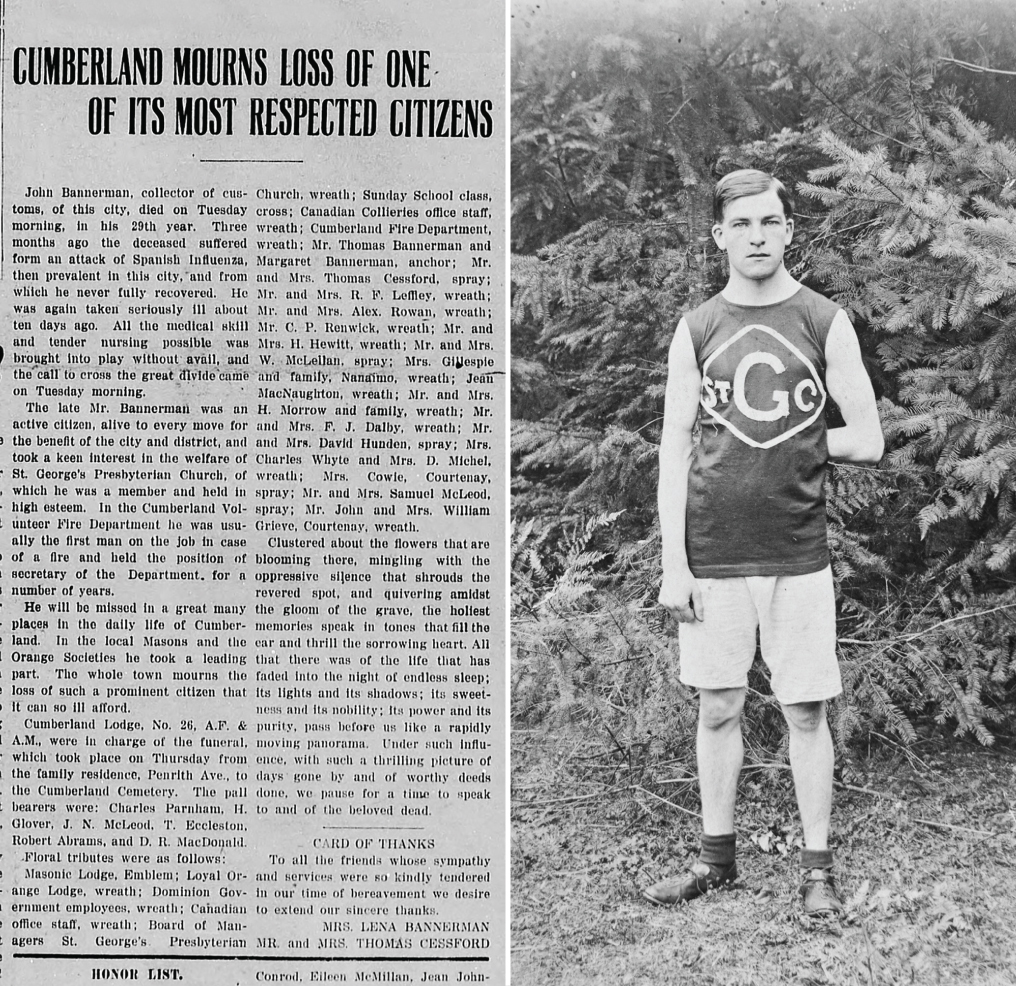

By all accounts, Johnny Bannerman is a very nice young man. He’s a member of the Cumberland Volunteer Fire Department, a devout churchgoer, and a Mason.

Naturally athletic, like all the Bannermans, he plays lacrosse, basketball, and baseball—and runs fast enough to have the Alberni Volunteer Fire Department jokingly call him a “ringer.” In the Island firefighting competition in September 1914, he smoked the competition in his events, securing the Island Cup for Cumberland. He’s that fast.

There have been a few hard years in the Comox Valley. The Big Strike from 1912 to 1914 left bitter feelings among the local coal miners, and the declaration of war in the fall of 1914 sent the men grudgingly back to work as essential contributors to the war effort—or off overseas to fight.

The Cumberland Islander has posted obituaries for all the Comox Valley boys killed in action in Europe, but the fighting is winding down by the fall of 1918. Johnny is looking forward to the end of the war and a return to normal life. He’s recently married, and just confirmed in a secure job as a customs officer.

The war news changes from wounded and dead to talk of peace treaties, then front pages start reporting occurrences of a deadly strain of influenza, like nothing ever seen before: the “Spanish flu,” they call it, although it didn’t originate in Spain. In bad cases, pneumonia, then death, follow in quick succession. It seems to affect the young and healthy, and people are falling ill at alarming rates, including soldiers who survived the horrific war only to succumb to death at home.

Between mid-September and December 1918, 500 million people worldwide will be infected by the Spanish flu. Ultimately, 50 million (some sources say up to 100 million) people will die. (We know now that it was an H1N1 influenza strain that was worse for young people because their stronger immune systems resulted in fiercer reactions as the body tried to fight off infection.)

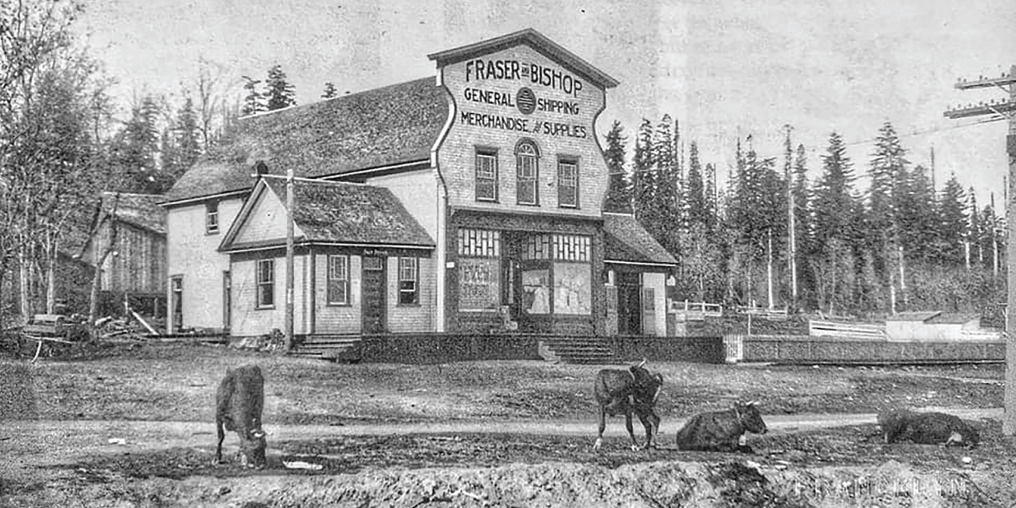

PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE CUMBERLAND FIREHALL (LEFT) AND KIM BANNERMAN (RIGHT)

By October 5, 1918, with 50 cases in Victoria, a provincial Order in Council closes theatres, schools, churches, and other public gathering spaces throughout British Columbia. The disease, however, spreads along rail lines and steamship routes. It targets the overcrowded living conditions of the lumber camps, the mines, and the canneries, and spreads its deadly trail to Asian and immigrant communities and First Nations settlements.

Ultimately, of the estimated 4,000 people who die of Spanish flu in BC in 1918-19, more than 25 per cent are First Nations. This appalling tragedy is made worse by the fact that First Nations people only make up about 5 per cent of the province’s population at the time: in 1918, out of British Columbia’s total population of 464,000, approximately 25,000 are First Nations.

Over the course of the flu, one in three people province-wide are infected. Johnny Bannerman is one of them. He falls ill in November—maybe from exposure at work at the Customs Office, where he deals with many strangers and people from abroad doing business—or maybe after the big welcome for returning troops at the railway station in Cumberland after the Armistice Parade.

He is slow to recover. Perhaps he tries a number of remedies: there are tonics and patent medicine by the dozens. But none is effective in preventing or curing the Spanish flu. Quinine in water, quinine in whisky; cinnamon bark; salt-water gargles; rum; Lysol added to your bath; Hamlin’s Wizard Oil; cod liver oil; malt extract with iron; tea made of fermented sage brush; devil’s club; swamp gooseberry; and water hemlock are all tried. For recovering influenza patients, egg water is recommended: one pint of cold water and two to four whipped egg whites, flavoured with salt or cinnamon.

Cumberland’s isolation hospital is too small to handle the influx of cases, so upstairs at the King George Hotel, 24 beds are prepared. The public school becomes an emergency hospital and teachers are trained as nurses. The new Lun Ying Club (Chinese Masonic Hall), which opened in September 1918 in the Chinatown area outside Cumberland, is used as a hospital for Chinese miners.

In the space of two months, more than 300 people die of the Spanish flu on Vancouver Island, including 10 or more from the Comox Valley. But by December 1918, the worst seems to be over and life is slowly returning to normal for many.

Not for Johnny Bannerman. Like so many others, he dies of complications from influenza in February 1919. He is 28 years and 11 months old.

“All the medical skill and tender nursing possible was brought into play without avail, and the call to cross the great divide came on Tuesday morning.” (Cumberland Islander, February 15, 1919 edition)