I enjoy the practice of traditional karate for many reasons, including what it teaches me about Japanese and Okinawan culture. But it could be considered surprising, given my family’s history with the Japanese, that this practice has become such an influential part of my life.

World War II was a global calamity, and it was catastrophic for countless families, including my own. Specifically, the conflict between the British and the Japanese created intergenerational ripples for my grandparents, my parents, and myself that took decades to reconcile.

From 1940 to 1942, my grandfather, Howard Newton, a captain in the British army, fought against Japanese Imperial forces in Malaysia. As an officer, he had been permitted to have his family near him in Singapore. In fact, my father was born there in 1940.

The Malaysian campaign was a success for the Japanese, but it was a blow to the Allies: about 10,000 were killed and 150,000 were captured, including my grandfather. He spent more than three years as a prisoner of war under severe conditions: a starvation diet, hard labour, and continual abuse. He wrote about his experiences as a prisoner of war (POW) in a fictionalized memoir, Hell’s Bonfire, published in the 1960s. After reading it, I believe that my grandfather lived with PTSD because of his time in the POW camps.

After Howard’s capture, my grandmother, Kathleen, and her two children—my father and his sister—were evacuated from Singapore to Australia and eventually to Ireland, where my grandmother had been raised. For the remainder of the war, they did not know whether my grandfather was alive. It was a particularly awful time for my father, who, as a small child, was abused by an older cousin. These experiences tormented him through much of his life and were the source of alcoholism and anger that disrupted my own childhood.

In August 1945, after the atomic bombings by the United States, the Japanese army surrendered and released their POWs. Howard returned to his home in Penrith, Cumberland County, UK. Eventually he wrote my grandmother to ask for a divorce: he was living with the widow of his brother, who had been killed in the war.

It’s not difficult to understand that these two people, so deeply affected by the war, would find comfort with each other. Howard abandoned his family, and he was never again in my father’s life. Bitter at the loss of her husband, which she blamed on the Japanese, my grandmother passed a hatred of them on to my father. When I was young, she would send me British comics set in World War II that depicted the Japanese and Germans in racist and degrading ways.

I could understand the source of my father’s and grandmother’s animosity, but I could not feel it myself. In fact, I was curious about the Japanese people and culture.

At university, I read Joy Kogawa’s poignant novel Obasan, which is based on her experience of being forced to move from her family home in coastal British Columbia (BC) in 1942 to be interned in camps for the remainder of the war. It was the first I had heard of the internment, and I began to view the history of Canada, inclusive of many racial injustices, in a new light.

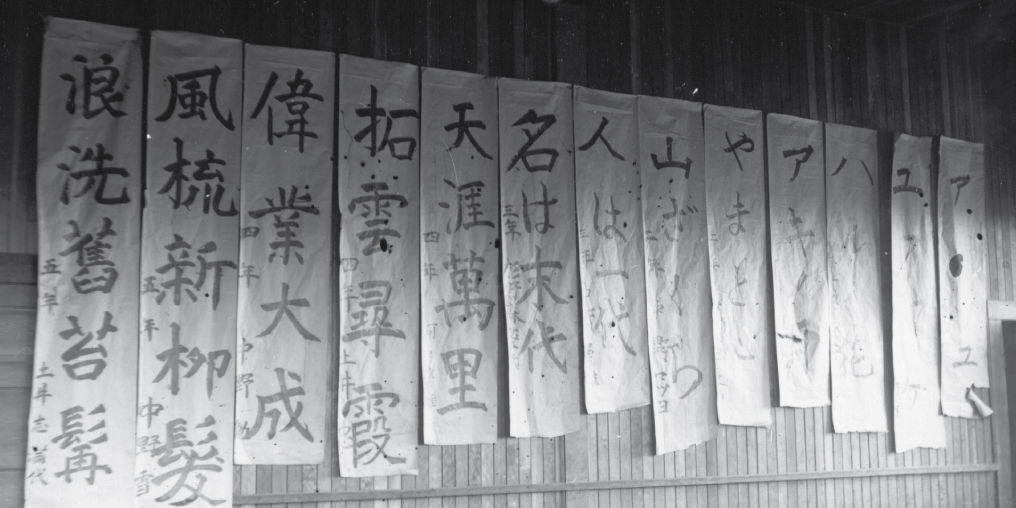

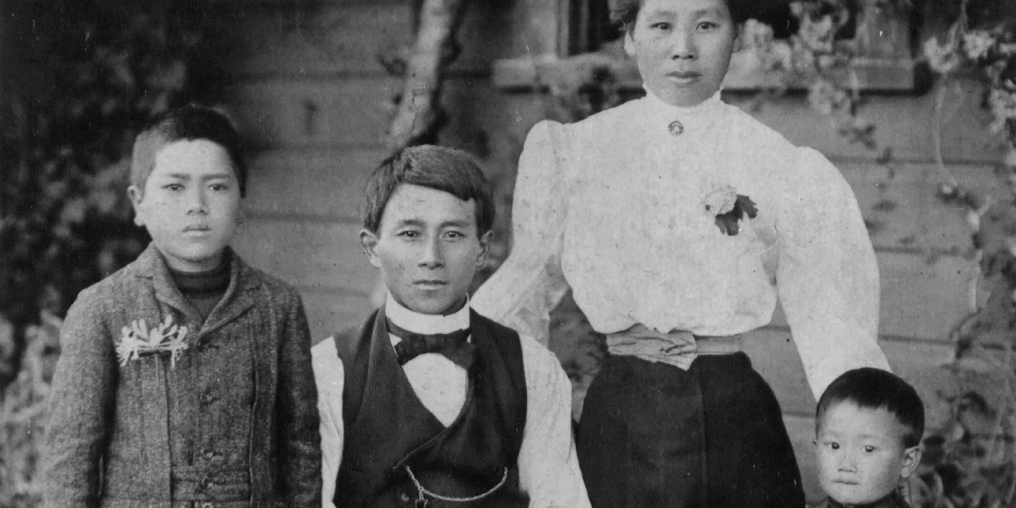

FEATURED PHOTO: C140-355. ABOVE: C140-368. COURTESY OF CUMBERLAND MUSEUM & ARCHIVES

About 10 years after reading Obasan, I moved to Vancouver Island from Ontario. I noticed the meagre signs of Japanese immigrant settlements on the island: a mural in Chemainus, a chimney stack in the woods in Paldi near Lake Cowichan, the overgrown No. 1 Japanese Town site near Cumberland. I wondered where the people had gone.

Not long afterwards, I went back to visit my family in Ontario. My father and I went out for a game of golf, and at the first tee, a Japanese man about my father’s age asked if he could join us for the round. I knew that my father would be reluctant. He said nothing, and so I welcomed the man to join us.

During the round, when I told the man I was visiting from Vancouver Island, he said he had been born in Chemainus, but when he was one year old, his family was removed to a camp in the interior of BC.

At the end of the war, his parents refused to remain in BC—a place where their store, their house, and their possessions had been seized and sold. They moved to Ontario and never returned.

On the drive home from the golf course, my father said, “His family went through terrible times in the war, too.” It was the beginning of some empathy and the end of some hatred.

My interest in Japanese culture brought me to karate as a young man. I am a product of my British and Irish heritage, for sure, but my experiences with traditional goju-ryu karate and kobudo (classical martial arts with weapons) have brought wonderful sensei (teachers) into my life, and I have had the opportunity to travel to Okinawa, Japan, many times.

My grandparents and my father hated the Japanese—empathy for people on the other side being one of the casualties of war. But all people have stories, and it’s through the sharing of these experiences that understanding and respect for other cultures develop, though often generations pass before the understanding and empathy take hold.