Owls are a fascinating subject rife with symbolism, mythology, and contentious conservationism. No Halloween would be complete without an owl swooping into the scene (not to steal the thunder from bats, of course). Owls are historically associated with wisdom, death, and the underworld. At one time, standard Canadiana education required reading Margaret Craven’s I Heard the Owl Call My Name—the book tells of how, according to Kwakwaka’wakw legend, an owl calling your name signaled imminent death.

My own experience with owls began jarringly, when a large barred owl crashed headlong into our F350 truck on a remote road out to the cabin when I was in my youth. My mother optimistically felt it could be still alive because “owls can rotate their heads almost in a full circle.” Many permits later, the taxidermist proved her wrong about its chances of survival. It still serves as a hauntingly beautiful memory, and set our family on a journey to find out as much as we could about these largely elusive creatures. We made huge owl birdhouses that almost claimed our own lives as we lugged them up into the high canopy of our tallest trees. We went on “owl prowls,” forgoing sleep and inviting ridicule from my peers as we became the weird family who creeped around at night calling out, “Who cooks for you?”—the standard barred owl call. Over time, owls became less a symbol of death for me as one of determination, luck, and a rodent-free hayfield.

Owls have evolved to have very unusual features. This is likely on account of having been around an exceptionally long time—since the early Eocene period some 57-60 million years ago, give or take. In this time, they have become highly efficient predators. It’s a common misconception that owls only hunt at night, and although they have excellent night vision on account of their large pupils, many hunt during the day. Their facial features and plumage are elliptically shaped to direct sound toward their ears. The ear placement is asymmetrical so there are slight differences in reception time, which allows them to identify the location of sound with greater precision. Unlike the noisy wings of the louder bird ilk (I’m talking to you, raven), owl feathers are silent in flight. The leading edge is like a comb, and the trailing edge is uneven. As such there is less turbulence and less sound, so they can deliver death to rodents, snakes, etc. with their sharp talons silently from above.

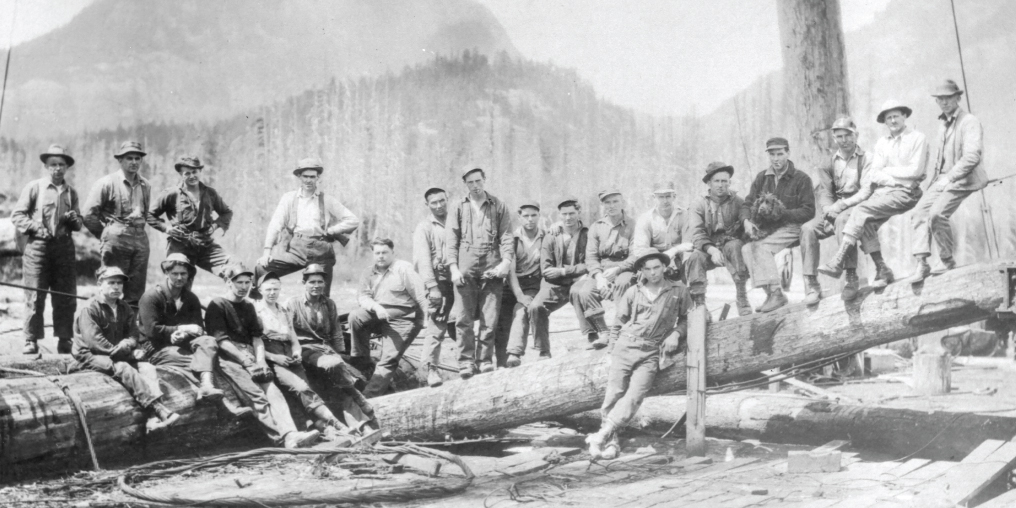

They are awfully coincidental, too. The night I was approached to write an article concerning them, a large form flew across my path. Getting closer to its perch I became excited, thinking to myself that I had seen a barn owl (Tito alba), a species that comes from one of the two main families of owls (the Tytonidae), and is at risk. Alas, it was the more bold and invasive barred owl (Strix varia) of the family of true owls (Strigidae). While beautiful in nature and decidedly more gregarious, the barred owl has also been implicated in the decline of the tiny western screech owl (Megascops kennicottii), a diminuative creature that I’ve been fortunate enough to spot on the trail out to Comox Lake from Cumberland. This owl has a small stature, two tufted ears and a distinct call—a tremolo, which is often like a bouncing ball from the male or the whinnying reply from the female which sounds not unlike a tiny horse up in the trees. The barred owl outperforms these smaller owls, as well as the endangered northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) for prey, by fighting to the death, or by infringing on important nesting space—the hollows of large old growth or second growth trees. This habitat is critical to the success of owls, and has often been a contentious front between loggers, developers, and ecologists.

Intrepid birders searching BC’s south coast may also be fortunate enough to see the great horned owl (Bubo virginianus), short-eared owl (Asio flammeus), long-eared owl (Asio otus), snowy owl (Bubo scandiacus), great grey owl (Strix nebulosa), northern saw-whet owl (Aegolius acadicus), northern pygmy owl (Glaucidium californicum), or the hawk owl (Surnia ulula).

For those who have fought a running battle trying to keep mice and rats at bay, thank an owl for doing its part. We should consider the importance of keeping their habitat intact to maintain this delicate balance that may exist out of sight, but certainly not out of earshot on those cool, dark, fall nights when furry things are trying to creep into your pantry.